|

|

| Res. Plant Dis > Volume 27(4); 2021 > Article |

|

ņÜö ņĢĮ

Pseudoperonospora cubensisļŖö ņśżņØ┤ļź╝ ĒżĒĢ©ĒĢ£ ļ░ĢĻ│╝ņ×æļ¼╝ņŚÉ Ļ░ĢĒĢ£ ļ│æņøÉņä▒ņØä ļéśĒāĆļéĖļŗż. ņØ┤ļ¤¼ĒĢ£ ļģĖĻĘĀļ│æņØś ņ╣£ĒÖśĻ▓Į ļ░®ņĀ£ļź╝ ņ£äĒĢśņŚ¼ ņØ┤ņé░ĒÖöņŚ╝ņåīņłśļź╝ ņĀüņÜ®ĒĢśņśĆļŖöļŹ░, ĒؼņäØ ļČäļ¼┤ņé┤ĒżĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ņŚÉ 41.2%ņØś ļ░®ņĀ£ĒÜ©Ļ│╝Ļ░Ć ņ׳ņŚłņ¦Ćļ¦ī, Ļ░ĆņŚ┤ņŚ░ļ¦ēņé┤ĒżĒĢ£ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ņŚÉļŖö 80.9%ņØś ļåÆņØĆ ļ░®ņĀ£ĒÜ©Ļ│╝ļź╝ ņ¢╗ņØä ņłś ņ׳ņŚłļŗż. ņØ┤ļ¤¼ĒĢ£ Ļ▓░Ļ│╝ļĪ£ ļģĖĻĘĀļ│æĻ│╝ Ļ░ÖņØ┤ ņŖĄļÅäņŚÉ Ēü░ ņśüĒ¢źņØä ļ░øļŖö ļ│æĒĢ┤ņØś ņ╣£ĒÖśĻ▓Į ļ░®ņĀ£ ņŗ£ ņŚ░ļ¦ē ļ░®ņĀ£ļŖö ĻĖ░ņĪ┤ņØś ĒؼņäØņé┤Ēż ļ░®ņĀ£ļ▓Ģļ│┤ļŗż ļŹöņÜ▒ ĒÜ©Ļ│╝ņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ņĀüņÜ® Ļ░ĆļŖźĒĢ£ Ļ▓āņØä ĒÖĢņØĖĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ņŚłļŗż.

ABSTRACT

Pseudoperonospora cubensis (downy mildew) is highly virulent to various Cucurbitaceae crops, including cucumber (Cucumis sativus). We tested chlorine dioxide application in a plastic greenhouse for environmentfriendly control of downy mildew disease. Spraying diluted chlorine dioxide suppressed downy mildew disease with 41.2% control efficacy. Thermal fogging with chlorine dioxide had a high control efficacy of 80.9%, confirming that this approach is useful for environment-friendly downy mildew control. Using thermal fogging to control diseases that are greatly affected by humidity, such as downy mildew, may be more effective compared with conventional dilution spray control methods.

ņÜ░ļ”¼ļéśļØ╝ ņśżņØ┤ ņ×¼ļ░░ļ®┤ņĀüņØĆ 4,962 haņØ┤ļ®░(ļģĖņ¦Ć 999, ņŗ£ņäż 3,963) ņŚ░Ļ░ä ņāØņé░ļ¤ēņØĆ 366ņ▓£Ēåż(ņŗ£ņäż 324,815 t, ļģĖņ¦Ć 41,250 t)ņ£╝ļĪ£, ļīĆļČĆļČä ņŗ£ņäżņ×¼ļ░░ļĪ£ ņāØņé░ļÉ£ļŗż(Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, 2020). Ēśäņ×¼Ļ╣īņ¦Ć ņÜ░ļ”¼ļéśļØ╝ņŚÉ ļ░£ņāØĒĢśļŖö ņśżņØ┤ņØś ļ│æĒĢ┤ļŖö 34ņóģņØś ļ│æņøÉņ▓┤Ļ░Ć Ļ┤ĆņŚ¼ĒĢśņŚ¼ 29ņóģņØ┤ ļ│┤Ļ│ĀļÉśņ¢┤ ņ׳ļŗż(Korean Society of Plant Pathology, 2009). ņØ┤ ņżæ ņĀä ņäĖĻ│äņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ļ░£ņāØĒĢśļŖö Pseudoperonospora cubensisņŚÉ ņØśĒĢ£ ļģĖĻĘĀļ│æņØĆ ņśżņØ┤, ļ®£ļĪĀ, ņ░ĖņÖĖ, ņłśļ░Ģ, ĒśĖļ░Ģ ļō▒ ļ░ĢĻ│╝(Cucurbitaceae) ņ×æļ¼╝ņŚÉņä£ ļ░£ņāØĒĢśļ®░(Kim ļō▒, 2003), ņ×ÄņØś ĒÖ£ļĀź ņĀĆĒĢś ļ░Å ņĪ░ĻĖ░ļéÖņŚĮņØä ņ£ĀļÅäĒĢśņŚ¼ Ļ│╝ņŗżņØś ĒÆłņ¦łņØä ļ¢©ņ¢┤ļ£©ļ”¼ļŖö ļ¦żņÜ░ ņŗ¼Ļ░üĒĢ£ Ēö╝ĒĢ┤ļź╝ ņØ╝ņ£╝Ēé©ļŗż(Lee ļō▒, 2013a). ņÜ░ļ”¼ļéśļØ╝ ņśżņØ┤ņØś ņ×¼ļ░░ļŖö ņŻ╝ļĪ£ ņŗ£ņäżņ×¼ļ░░ļĪ£ ņŗ£ņäżĒĢśņÜ░ņŖż ļé┤ņØś ĒÖśĻ▓ĮņĪ░Ļ▒┤ņØ┤ ļ│æ ļ░£ņāØņØä ņóīņÜ░ĒĢśļ®░(Park ļō▒, 1996), ļģĖĻĘĀļ│æņŚÉ Ļ▒Ėļ”░ ņśżņØ┤ļŖö ņ×ÄņŚÉ ļŗżĻ░üĒśĢņØś ļģĖļ×Ćņāē ļ│æļ░śņØ┤ ĒśĢņä▒ļÉśļ»ĆļĪ£ ņØ┤ ļ│æņ¦Ģņ£╝ļĪ£ ļ│æ ļ░£ņāØņØä ņ¦äļŗ©ĒĢśĻĖ░ļŖö ņłśņøöĒĢ£ ņĀÉņØ┤ ņ׳ņ£╝ļéś ņØ╝ļŗ© ļ░£ļ│æĒĢśļ®┤ ņłśņØ╝ ļé┤ Ēżņן ņĀäņ▓┤ļĪ£ ĻĖēņåŹĒ׳ ļ▓łņ¦ĆĻĖ░ ņŗ£ņ×æĒĢśņŚ¼ ļ░®ņĀ£Ļ░Ć ņ¢┤ļĀżņøīņ¦Ćļ»ĆļĪ£ ļ│æ ļ░£ņāØ ņ┤łĻĖ░ņØś ļ░®ņĀ£Ļ░Ć ļ¦żņÜ░ ņżæņÜöĒĢśļŗż(Kim ļō▒, 2003). ņØ┤ļ¤¼ĒĢ£ ņØ┤ņ£ĀļĪ£ ņśżņØ┤ ļģĖĻĘĀļ│æņØś ļ░®ņĀ£ļŖö ņĀĆĒĢŁņä▒ ĒÆłņóģņØä ņØ┤ņÜ®ĒĢśĻ▒░ļéś ĒÖöĒĢÖņĢĮņĀ£ņŚÉ ņØśĒĢ£ ļ░®ņĀ£ņŚÉ ņØśņĪ┤ĒĢ┤ ņÖöļŖöļŹ░(Savory ļō▒, 2011), ņØ╝ļ░śņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ļåŹĻ░ĆņØś Ļ▓ĮĒŚśņŚÉ ņØśĒĢ£ ņśłļ░®ņĀü Ļ┤Ćļ”¼ņŚÉ ņØśņĪ┤ĒĢśĻ▓ī ļÉśļ®░ ņØ┤ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ Ļ│╝ļÅäĒĢ£ ņĢĮņĀ£ņØś ņé┤Ēżļź╝ ļÅÖļ░śĒĢ£ļŗż. ĻĘĖ Ļ▓░Ļ│╝ ļåŹņĢĮņ×öļźśņØś ņ£äĒŚśņØä Ēö╝ĒĢśĻĖ░ ņ¢┤ļĀĄĻ│Ā, ļģĖĻĘĀļ│æ ļ░®ņĀ£ņŚÉ ņé¼ņÜ®ļÉ£ ļ®öĒāĆļØĮņŗż, ņĢäņĪ▒ņŗ£ņŖżĒŖĖļĪ£ļ╣ł, Ēü¼ļĀłņåŹņŗ¼ļ®öĒŗĖ, Ēö╝ļØ╝Ēü┤ļĪ£ņŖżĒŖĖļĪ£ļ╣ł ļō▒ ĒÖöĒĢÖļåŹņĢĮņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ņĀĆĒĢŁņä▒ĻĘĀņØ┤ ņČ£ĒśäĒĢśņŚ¼(LebedaņÖĆ Cohen, 2012; Meng ļō▒, 2017; UrbanĻ│╝ Lebeda, 2006; Zhao ļō▒, 2012) ĒÜ©Ļ│╝ņĀüņØĖ ļ░®ņĀ£Ļ░Ć ņØ┤ļŻ©ņ¢┤ņ¦Ćņ¦Ć ņĢŖļŖö Ļ▓ĮņÜ░Ļ░Ć ļ¦ÄĻĖ░ ļĢīļ¼ĖņŚÉ ņśżņØ┤ ļģĖĻĘĀļ│æņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ņ╣£ĒÖśĻ▓ĮņĀüņØĖ ļ░®ņĀ£ļ▓Ģ Ļ░£ļ░£ņØ┤ ĒĢäņÜöĒĢ£ ņŗżņĀĢņØ┤ļŗż.

ņśżņØ┤ ļģĖĻĘĀļ│æņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ņāØļ¼╝ņĀü ļ░®ņĀ£ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļĪ£ļŖö ļ»ĖņāØļ¼╝ļåŹņĢĮ Bacillus subtillis KB-401ņÖĆ B. subtillis DBB-15011ļź╝ Ēś╝ņÜ®ĒĢśņŚ¼ 70% ļ░®ņĀ£ĒÜ©Ļ│╝ļź╝ ĒÖĢņØĖĒĢ£ Ļ▓░Ļ│╝ņÖĆ(Kim ļō▒, 2011), Bacillus amyloliquefaciens subsp. plantarum CC110 ĻĘĀņŻ╝ļŖö ņśżņØ┤ ļģĖĻĘĀļ│æĻĘĀņØś Ēżņ×ÉļéŁ ļ│ĆĒśĢņØä ņ£Āļ░£ĒĢśņŚ¼ ļ░£ņāØņØä ņ¢ĄņĀ£ĒĢ£ļŗżļŖö Ļ▓░Ļ│╝Ļ░Ć ļ│┤Ļ│ĀļÉśņŚłļŗż(Lee ļō▒, 2013c). ļŗżļźĖ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļōżņØä ņé┤ĒÄ┤ļ│┤ļ®┤ ņØīņØ┤ņś©ņä▒ Ļ│äļ®┤ĒÖ£ņä▒ņĀ£ņØĖ sodium dodecylbenzene sulfonateļŖö ļģĖĻĘĀļ│æņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ņśłļ░® ĒÜ©Ļ│╝Ļ░Ć ņÜ░ņłśĒĢśņŚ¼ ļ│æņøÉĻĘĀ ņĀæņóģ ņĀä ņ▓śļ”¼ļĪ£ 85%ņØś ļ░®ņĀ£ĒÜ©Ļ│╝ļź╝ ĒÖĢņØĖĒĢśņśĆļŗż(Choi ļō▒, 2004). ņĢäņØĖņé░ņŚ╝(phosphorous acid)ņØĆ Ļ▓ĮņŚĮ ņ▓śļ”¼ņŗ£ ņśżņØ┤ ļģĖĻĘĀļ│æņØä 82% ļ░®ņĀ£ĒĢśņśĆņ£╝ļ®░, ņśżņØ┤ņØś ņāØņ£Ī ļśÉĒĢ£ ņ┤ēņ¦äĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ĒÖĢņØĖļÉśņŚłļŗż(Chang ļō▒, 2000). ņØ┤ ņÖĖņŚÉļÅä ņĀĆĒĢŁņä▒ ĒÆłņóģĻ│╝ ļ│┤ļź┤ļÅäņĢĪ ļō▒ ņ£ĀĻĖ░ļåŹņŚģņ×Éņ×¼ņØś ņØ┤ņÜ®(Kim ļō▒, 2018; Lee ļō▒, 2013a), ņł£ņ¦Ćļź┤ĻĖ░ņÖĆ Ļ░ÖņØĆ ņ×¼ļ░░ņĀü ļ░®ļ▓ĢņØä ņØ┤ņÜ®ĒĢ£ ļ░®ņĀ£(Park ļō▒, 2016)ļō▒ ļŗżņ¢æĒĢ£ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼Ļ░Ć ņłśĒ¢ēļÉśņ¢┤ņÖöņ¦Ćļ¦ī ļåŹĻ░ĆņŚÉņä£ ņŗżņÜ®ĒÖöļÉ£ Ļ▓░Ļ│╝ļŖö ļ¦Äņ¦Ć ņĢŖļŗż.

ņØ┤ņé░ĒÖöņŚ╝ņåīņłśļŖö ņŗØĒÆł ļ░Å ĒÖśĻ▓ĮņØś Ēæ£ļ®┤ņØä ņåīļÅģĒĢśĻĖ░ ņ£äĒĢ£ ĻĖ░ņĪ┤ņØś ņŚ╝ņåīņåīļÅģņŚÉ ļ╣äĒĢ┤ ļ¼╝ņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ņÜ®ĒĢ┤ņä▒ņØ┤ 10ļ░░ ļåÆĻ│Ā ņé░ĒÖöļĀźļÅä 2.5ļ░░ Ļ░ĢĒĢśņŚ¼ ņśżņŚ╝ļ¼╝ņ¦łņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ļČäĒĢ┤ ļŖźļĀźĻ│╝ ņé┤ĻĘĀļĀźņØ┤ ņÜ░ņłśĒĢ£ Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ņĢīļĀżņĀĖ ņ׳ļŗż(Ryu, 2007). ņÜ░ļ”¼ļéśļØ╝ņŚÉņä£ļÅä ņØ┤ļ¤¼ĒĢ£ ņé┤ĻĘĀļĀźņ£╝ļĪ£ ņØĖĒĢśņŚ¼ 2007ļģä Ļ░Ģņé░ņä▒ņ░©ņĢäņŚ╝ņåīņé░ņłś, ļ»Ėņé░ņä▒ņ░©ņĢäņŚ╝ņåīņé░ņłśņÖĆ ĒĢ©Ļ╗ś ņØ┤ņé░ĒÖöņŚ╝ņåīņłśĻ░Ć Ļ│╝ņŗżļźśņÖĆ ņ▒äņåīļźśņØś ņé┤ĻĘĀņĀ£ļĪ£ ņ¦ĆņĀĢļÉśņŚłņ£╝ļ®░(Park ļō▒, 2012), ņĄ£ĻĘ╝ņŚÉļŖö ņ×æļ¼╝ ļ│æ ļ░®ņĀ£ņÜ® ņ£ĀĻĖ░ļåŹņŚģņ×Éņ×¼ļĪ£ ļō▒ļĪØļÉśņŚłļŗż(National Agricultural Products Quality Management Service, 2021). ņØ┤ņé░ĒÖöņŚ╝ņåī(ClO2)ļŖö ņŚ╝ņåīņÖĆ ņ£Āņé¼ĒĢ£ ņé┤ĻĘĀĻĖ░ņ×æņØä Ļ░¢Ļ│Ā ņ׳ņ¦Ćļ¦ī ĒĢäņÜöĒĢ£ ļåŹļÅäņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝ ĒؼņäØ ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŖö ņןņĀÉņØ┤ ņ׳ņ£╝ļ®░, Ļ░ĆņŚ┤ņé┤ĻĘĀņ▓śļ”¼Ļ░Ć ļČłĻ░ĆļŖźĒĢ£ ņŗĀņäĀ ņ▒äņåī ļō▒ņØś ļ»ĖņāØļ¼╝ ņĀ£ņ¢┤ņŚÉ ĒÜ©Ļ│╝ņĀüņØ┤ļŗż(Benarde ļō▒, 1965; Kim ļō▒, 2009). ļåŹņé░ļ¼╝ņŚÉ ņśżņŚ╝ļÉśņ¢┤ņ׳ļŖö ļ»ĖņāØļ¼╝ņØä ņĀ£ņ¢┤ĒĢśĻĖ░ ņ£äĒĢ£ ņØ┤ņé░ĒÖöņŚ╝ņåīņłś ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ Ļ▓░Ļ│╝ļĪ£ļŖö Ēö╝ļ¦ØņŚÉ ņĀæņóģļÉ£ Listeria monocytogenes ĻĘĀņØś ņ¢ĄņĀ£(Han ļō▒, 2001), ņżäĻĖ░ņāüņČöņØś Ļ░łļ│Ć ļ░Å ņ£ĀĒåĄĻĖ░ĒĢ£ Ē¢źņāüņØä ņ£äĒĢ£ ņØ╝ļ░śņäĖĻĘĀ ņäĖņ▓Ö(Chen ļō▒, 2010), ļīĆņןĻĘĀ ļ░Å Salmonella ņĀ£ņ¢┤ļź╝ ņ£äĒĢ£ ņ▓ŁĻ▓Įņ▒ä ņóģņ×É ņåīļÅģ(Choi ļō▒, 2016) ļō▒ņØ┤ ņ׳ļŗż. ņŗØļ¼╝ļ│æņøÉĻĘĀņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļĪ£ ņØ┤ņé░ĒÖöņŚ╝ņåīņłśļŖö 1.3 mg/lņØś ļåŹļÅäņŚÉņä£ Ļ┤ĆĻ░£ņłś ņżæņØś ļ¼┤ļ”äļ│æĻĘĀ(Erwinia carotovora subsp. carotovora) ļ░Å ĒÆŗļ¦łļ”äļ│æĻĘĀ(Ralstonia solancearum)ņØä 100% ļČłĒÖ£ņä▒ĒÖöņŗ£Ēé©ļŗżĻ│Ā ļ│┤Ļ│ĀļÉśņŚłļŗż(Yao ļō▒, 2010). ļśÉĒĢ£ ņØ┤ņé░ĒÖöņŚ╝ņåīņłśļŖö ņłśĒÖĢ Ēøä Ļ│╝ņŗżņØś ņĀĆņןņä▒ ņ”ØĻ░Ćļź╝ ļ¬®ņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ņé¼ņÜ®ļÉ£ļŗż(Mari ļō▒, 2003; Roberts, 1994). Lee ļō▒(2013b)ņØĆ ņśżļ»Ėņ×É ņłśĒÖĢ Ēøä ņØ┤ņé░ĒÖöņŚ╝ņåīņłśņØś ļåŹļÅäņÖĆ ņ▓śļ”¼ ņŗ£Ļ░äņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝ Ēæ£ļ®┤ņØś ļ»ĖņāØļ¼╝ ņĀĆĻ░É ĒÜ©Ļ│╝Ļ░Ć ņ׳ļŖö Ļ▓āņØä ĒÖĢņØĖĒĢśņśĆļŗż. ļö░ļØ╝ņä£ ļ│Ė ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ļŖö ņÜ░ņłśĒĢ£ ņé┤ĻĘĀļĀźņØä Ļ░¢Ļ│Ā ņ׳ņ£╝ļ®░, ņ╣£ĒÖśĻ▓ĮņĀü ļ│æĒĢ┤ Ļ┤Ćļ”¼Ļ░Ć Ļ░ĆļŖźĒĢ£ ņØ┤ņé░ĒÖöņŚ╝ņåīņłśļź╝ ņØ┤ņÜ®ĒĢśņŚ¼ ņśżņØ┤ ļģĖĻĘĀļ│æņØä ĒÜ©Ļ│╝ņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ļ░®ņĀ£ĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ļŖö ņ▓śļ”¼ļ▓Ģ, ļ░®ņĀ£ĒÜ©Ļ│╝ ļō▒ņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ Ļ▓Ćņ”ØņØä ĻĘĖ ļ¬®ņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ĒĢ£ļŗż.

ļ░®ņĀ£ĒÜ©Ļ│╝ Ļ▓ĆņĀĢ. ņśżņØ┤ ļģĖĻĘĀļ│æ ļ░®ņĀ£ĒÜ©Ļ│╝ļź╝ Ļ▓ĆņĀĢĒĢśĻĖ░ ņ£äĒĢśņŚ¼ ņČ®ņ▓Łļé©ļÅäļåŹņŚģĻĖ░ņłĀņøÉ ļé┤ ņŗ£ņäżĒżņן(260 m2) 3Ļ░£ņåīļź╝ ņØ┤ņÜ®ĒĢśņśĆļŗż. ņśżņØ┤ņØś ĒÆłņóģņØĆ ļ░▒ļŗżļŗżĻĖ░ļź╝ ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢśņśĆĻ│Ā, ņĀĢņŗØ Ļ▒░ļ”¼ļŖö 120├Ś40 cmļĪ£ 5ņøö ņżæņł£ ņĀĢņŗØĒĢśņśĆļŗż. ņŗ£ĒŚśņØä ņłśĒ¢ēĒĢ£ ņŗ£ņäżĒżņןņØĆ ņŗ£ĒŚś 1ļģä ņĀäļČĆĒä░ ņśżņØ┤ļź╝ ņ×¼ļ░░ĒĢśņśĆĻ│Ā, 5ņøö ņĀĢņŗØļČĆĒä░ 7ņøö ņłśĒÖĢ, 8ņøö ņĀĢņŗØļČĆĒä░ 10ņøö ņłśĒÖĢ ļō▒ 2ĒÜīņØś ņ×¼ļ░░ĻĖ░Ļ░ä ņżæ ļģĖĻĘĀļ│æņØĆ ņĀĢņŗØ 25ņØ╝ ĒøäļČĆĒä░ ņ×ÉņŚ░ļ░£ļ│æĒĢśņŚ¼ ļ░®ņĀ£ņŗ£ĒŚśņØä ņłśĒ¢ēĒĢśĻĖ░ ņČ®ļČäĒĢ£ ļ░£ļ│æļÅäļź╝ ļ│┤ņśĆļŗż. ņØ┤ņé░ĒÖöņŚ╝ņåīņłś ņ▓śļ”¼ ļ░®ļ▓ĢņØĆ ĒؼņäØļČäļ¼┤ņé┤ĒżņÖĆ Ļ░ĆņŚ┤ņŚ░ļ¦ēņ▓śļ”¼ļĪ£ ĻĄ¼ļČäĒĢśņŚ¼ ņĀĢņŗØ 20ņØ╝ ĒøäļČĆĒä░ 1ņŻ╝ Ļ░äĻ▓®ņ£╝ļĪ£ 4ĒÜī ņ▓śļ”¼ĒĢśņśĆļŗż. ņØ┤ņé░ĒÖöņŚ╝ņåīņłśļŖö ņé░ņåīĒāäĒöīļ¤¼ņŖż(Ļ│Ąņŗ£ 3-4-031, ņ£ĀĒÜ©ļåŹļÅä 3,000 ppm, Young Bio Lab, Daejeon, Korea)ļź╝, Ļ░ĆņŚ┤ņŚ░ļ¦ēņ▓śļ”¼ļź╝ ņ£äĒĢ£ ĒÖĢņé░ņĀ£ļŖö ĒĢśņ¢Ćļŗś(Ļ│Ąņŗ£-1-5-087, Ilkwangbio, Nonsan, Korea)ņØä ņé¼ņÜ®ĒĢśņśĆļŖöļŹ░, Ļ░ĆņŚ┤ņŚ░ļ¦ēņ▓śļ”¼ĻĄ¼ļŖö 260 m2 ļ®┤ņĀüņØś ņŗ£ņäżņŚÉ 3,000 ppm ļåŹļÅäņØś ņØ┤ņé░ĒÖöņŚ╝ņåīņłś 200 mlņÖĆ ĒÖĢņé░ņĀ£ 350 mlļź╝ Ēś╝ĒĢ®ĒĢśņŚ¼ Ļ░ĆņŚ┤ņŚ░ļ¦ēĻĖ░(ļČäļ¼┤ļ¤ē 40 l/hr, 911-Turbo, Ilkwangbio)ļĪ£ ņŚ░ļ¦ē ņé┤ĒżĒĢśņśĆļŗż. ĒؼņäØļČäļ¼┤ņé┤Ēż ņ▓śļ”¼ĻĄ¼ļŖö ņØ┤ņé░ĒÖöņŚ╝ņåīņłśļź╝ 1,000ļ░░ ĒؼņäØĒĢśņŚ¼ ļÅÖļĀźļČäļ¼┤ĻĖ░(30 kg/cm2)ļĪ£ ļČäļ¼┤ņé┤Ēż(0.5 l/m2)ĒĢśņśĆĻ│Ā, ļīĆņĪ░ĻĄ¼ļŖö ļ¼╝ņØä ļČäļ¼┤ņé┤ĒżĒĢśņśĆļŗż. ļīĆņĪ░ ņ▓śļ”¼ĻĄ¼ļŖö ļ¼╝ 200 mlņÖĆ ĒÖĢņé░ņĀ£ 350 mlļź╝ Ēś╝ĒĢ®ĒĢśņŚ¼ ņ▓śļ”¼ĒĢśņśĆļŗż. ņé┤ĒżļÉ£ ņŚ░ļ¦ēņØĆ ņŗ£ņäżĒĢśņÜ░ņŖżļź╝ ļ░ĆĒÅÉļÉ£ ņāüĒā£ļĪ£ 150ļČä ļÅÖņĢł ņ£Āņ¦ĆĒĢ£ Ēøä ĒÖśĻĖ░ĒĢśņśĆļŗż.

ņ▓śļ”¼ ļ░®ļ▓Ģļ│ä ņś©ņŖĄļÅä ņĪ░ņé¼. ļģĖĻĘĀļ│æ ļ░®ņĀ£ļź╝ ņ£äĒĢ£ ņØ┤ņé░ĒÖö ņŚ╝ņåīņłśņØś ņ▓śļ”¼ ļ░®ļ▓Ģļ│ä ĒÖśĻ▓Įļ│ĆĒÖöļź╝ ņĪ░ņé¼ĒĢśĻĖ░ ņ£äĒĢśņŚ¼ ĒؼņäØļČäļ¼┤ņé┤Ēż ņ▓śļ”¼ĻĄ¼ņÖĆ ņŚ░ļ¦ēņ▓śļ”¼ĻĄ¼ņŚÉ Ļ░üĻ░ü ņ¦Ćņāü 1 m ļåÆņØ┤ņŚÉ ņś©ņŖĄļÅäņĖĪņĀĢĻ│ä(testo 174H, Testo SE & Co., Titisee-Neustadt, Germany)ļź╝ ņäżņ╣śĒĢśņŚ¼ ņĢĮņĀ£ņ▓śļ”¼ ņĀäĒøäņØś ņś©ņŖĄļÅä ļ│ĆĒÖöļź╝ ĒÖĢņØĖĒĢśņśĆļŗż. Ļ▓ĆņČ£ Ļ░äĻ▓®ņØĆ 10ļČäņ£╝ļĪ£ ĒĢśņśĆĻ│Ā, ņ▓śļ”¼ ņĀäĒøä 210ļČä ļÅÖņĢłņØś ņ×ÉļŻīļź╝ ļ╣äĻĄÉĒĢśņśĆļŗż.

ļ░®ņĀ£ĒÜ©Ļ│╝ ņĪ░ņé¼. ņØ┤ņé░ĒÖöņŚ╝ņåīņłś ņ▓śļ”¼ĻĄ¼ņØś ļģĖĻĘĀļ│æ ļ░®ņĀ£ĒÜ©Ļ│╝ ņĪ░ņé¼ļŖö ņĄ£ņóģ ļ░®ņĀ£ņĀ£ ņ▓śļ”¼ 7ņØ╝ Ēøä ņĪ░ņé¼ĒĢśņśĆļŗż. ņĪ░ņé¼ĻĖ░ņżĆņØĆ ĻĄŁļ”ĮļåŹņŚģĻ│╝ĒĢÖņøÉņØś ļåŹņĢĮļō▒ļĪØņŗ£ĒŚś ņäĖļČĆņ¦Ćņ╣©(National Institute of Agricultural Sciences, 2018)ņŚÉ ļö░ļØ╝ ļ░£ļ│æļÅäļĪ£ ĒĢśņśĆņ£╝ļ®░, ņ▓śļ”¼ĻĄ¼ļŗ╣ 100ņŚĮ(ĻĄ¼ļŗ╣ 10ņŻ╝, ņŻ╝ļŗ╣ 10ņŚĮ)ņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ļ│æļ░śļ®┤ņĀüļźĀņØä ņĢäļלņØś ĻĖ░ņżĆņ£╝ļĪ£ ņĪ░ņé¼ĒĢ£ Ēøä ļ░£ļ│æļÅäļĪ£ ĒÖśņé░ĒĢśņśĆļŗż.

0: ļ░£ļ│æņŚåņØī

1: ļ│æļ░śļ®┤ņĀüļźĀ 1-5%

2: ļ│æļ░śļ®┤ņĀüļźĀ 5.1-20%

3: ļ│æļ░śļ®┤ņĀüļźĀ 20.1-50%

4: ļ│æļ░śļ®┤ņĀüļźĀ 50.1% ņØ┤ņāü

N: ņĪ░ņé¼ņŚĮņłś

ņØ┤ņé░ĒÖöņŚ╝ņåīņłśņØś ņ▓śļ”¼ ļ░®ļ▓Ģļ│ä ļ│æ ļ░£ņāØ ņĀĢļÅä ļ╣äĻĄÉļŖö R ĒöäļĪ£ĻĘĖļש version 4.1.1 (R Core Team, 2017)ņØä ņØ┤ņÜ®ĒĢśņŚ¼ Duncan ļŗżņżæĻ▓ĆņĀĢņ£╝ļĪ£ ņ£ĀņØśņä▒ņØä Ļ▓ĆņĀĢĒĢśņśĆļŗż.

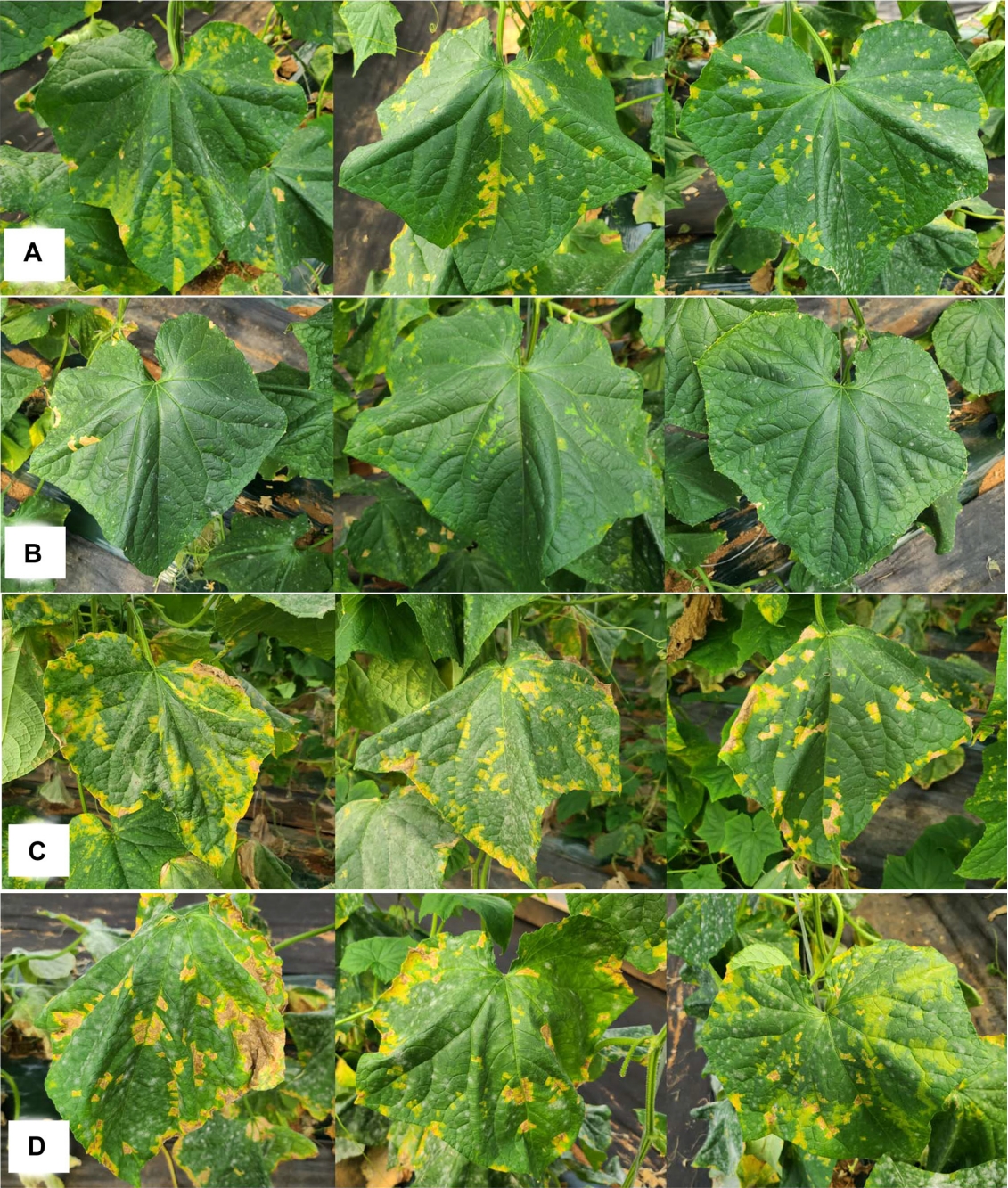

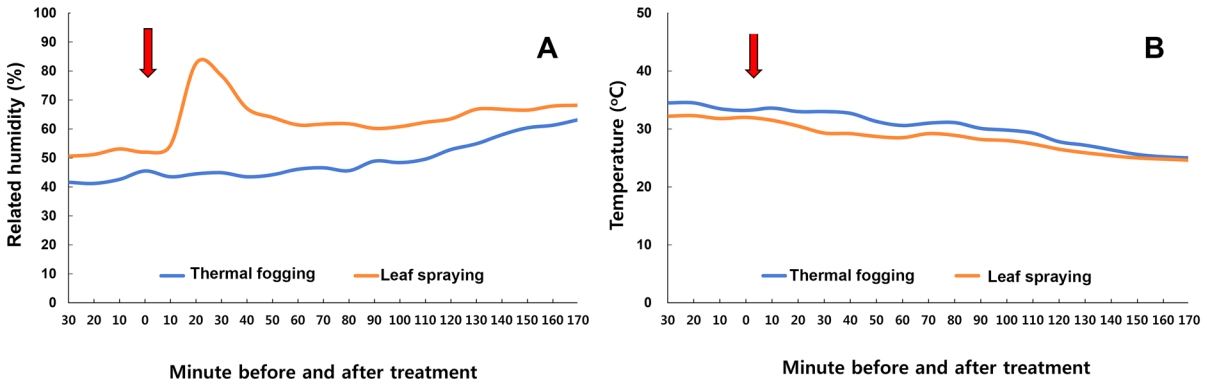

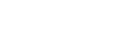

ņśżņØ┤ ļģĖĻĘĀļ│æņØĆ 5ņøö ņĀĢņŗØ ņØ┤Ēøä 6ņøö ņ┤łļČĆĒä░ ļ░£ļ│æņØ┤ ņŗ£ņ×æļÉ£ļŗż. ņ┤łĻĖ░ņŚÉļŖö ņåīĒśĢ ĒÖ®ņāē ļ░śņĀÉ(Fig. 1A)ņØä ĒśĢņä▒ĒĢśļ®┤ņä£ ņŗ£ņ×æļÉśļŖöļŹ░, ļŗżĻ░üĒśĢ ļ│æļ░śņØĆ ņ£ĀĒĢ®ļÉśņ¢┤ ĒÖĢļīĆļÉśĻ│Ā(Fig. 1B) ļéśņżæņŚÉļŖö Ļ│Āņé¼ļÉśļŖö ļ│æļ░śļČĆņ£äĻ░Ć ņ×Ä ņĀäņ▓┤ļĪ£ ĒÖĢļīĆļÉ£ļŗż(Fig. 1C). ņśżņØ┤ ļģĖĻĘĀļ│æņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ņ£ĀĻĖ░ļåŹņŚģņ×Éņ×¼ ņØ┤ņé░ĒÖöņŚ╝ņåīņłśņØś ļ░®ņĀ£ĒÜ©Ļ│╝ļź╝ ĒÖĢņØĖĒĢ£ Ļ▓░Ļ│╝, ņØ┤ņé░ĒÖöņŚ╝ņåīņłśļź╝ ĒؼņäØļČäļ¼┤ņé┤ĒżĒĢ£ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ļ░®ņĀ£ĒÜ©Ļ│╝ļŖö 41.5%ļĪ£ ļé«ņĢśļŗż(Table 1). ņ×ÄņŚÉ ĒśĢņä▒ļÉ£ ļģĖĻĘĀļ│æņØś ļ│æņ¦ĢņØĆ ļ│æļ░śņØś ņ£ĀĒĢ® ļ░Å ĒÖĢļīĆĻ░Ć ņØ╝ņ¢┤ļé¼Ļ│Ā, ņØ╝ļČĆ Ļ│Āņé¼ ļ│æļ░śļÅä ĒÖĢņØĖļÉśņŚłļŗż(Fig. 2A). ļģĖĻĘĀļ│æņØś ļ░£ļ│æņŚÉ ļ»Ėņ╣śļŖö ņś©ļÅä ļ▓öņ£äļŖö 5-28oCļĪ£ ļ╣äĻĄÉņĀü ļäōņ¦Ćļ¦ī, ņĄ£ņåī 2ņŗ£Ļ░ä ņØ┤ņāüņØś ņ×ÄņĀ¢ņØī ņŗ£Ļ░äņØ┤ ļ░£ļ│æņŚÉ ĒĢäņÜö(Lee ļō▒, 2013d)ĒĢśļ®░, ļ╣äĻ░Ć ļ¦ÄņØ┤ ņśżĻ│Ā ņŖĄĒĢ£ ņŗ£ĻĖ░ņŚÉ ļ░£ļ│æĻ│╝ ņĀäņŚ╝ņØ┤ ņ”ØĻ░Ć(Park ļō▒, 2016)ĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ņĢīļĀżņĀĖ ņ׳ļŗż. ļö░ļØ╝ņä£ ļ░®ņĀ£ļź╝ ņ£äĒĢ£ ĒؼņäØņĢĪņØś ļīĆļ¤ē ņé┤ĒżļŖö ņĀ£ĒĢ£ņĀüņØĖ ņŗ£ņäż ļé┤ņØś ņŖĄļÅäļź╝ ņāüņŖ╣ņŗ£ņ╝£ ĒÜ©Ļ│╝ņĀüņØĖ ļ░®ņĀ£ļź╝ ņĀĆĒĢ┤ĒĢśļŖö Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ĒīÉļŗ©ļÉśņŚłļŗż. ļśÉĒĢ£ ņśżņØ┤ ļģĖĻĘĀļ│æĻĘĀņØĆ ņāüļīĆņŖĄļÅä 90%ņØś ĒÖśĻ▓ĮņŚÉņä£ ļ¬ć Ļ░£ņØś Ēżņ×Éļ¦īņ£╝ļĪ£ļÅä ļģĖĻĘĀļ│æ ļ│æļ░śņØä ĒśĢņä▒ņŗ£Ēé¼ ņłś ņ׳ņ£╝ļ®░(Sun ļō▒, 2017), ņś©ļÅä, Ļ░ĢņÜ░ ļō▒ ļŗżņ¢æĒĢ£ ĒÖśĻ▓ĮņÜöņØĖ ņżæņŚÉņä£ ņāüļīĆņŖĄļÅäĻ░Ć ļģĖĻĘĀļ│æ ļ░£ļ│æņŚÉ Ļ░Ćņן ņżæņÜöĒĢ£ ņÜöņØĖņØ┤ļØ╝Ļ│Ā ļ│┤Ļ│ĀļÉ£ ļ░ö ņ׳ļŗż(Sharma ļō▒, 2003). ņŗżņĀ£ ļ│Ė ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņŚÉņä£ļÅä ņØ┤ņé░ĒÖöņŚ╝ņåīņłś ĒؼņäØņĢĪņØä ļČäļ¼┤ņé┤ĒżĒĢ£ ņ¦üĒøä ņŗ£ņäż ļé┤ņØś ņŖĄļÅäļŖö ĻĖēĻ▓®Ē׳ ņ”ØĻ░ĆĒĢśņŚ¼ ņĢĮ 2ņŗ£Ļ░ä ļÅÖņĢł ņāüļīĆņŖĄļÅäņØś ņāüņŖ╣ņØä ĒÖĢņØĖĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ņŚłļŗż(Fig. 3A). ļ░śļ®┤ ņØ┤ņé░ĒÖöņŚ╝ņåīņłśļź╝ ĒÖĢņé░ņĀ£ĒÖö Ēś╝ĒĢ®ĒĢśņŚ¼ Ļ░ĆņŚ┤ņŚ░ļ¦ēņé┤ĒżĒĢ£ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ņŚÉļŖö 80.9%ņØś ļåÆņØĆ ļ░®ņĀ£ĒÜ©Ļ│╝ļź╝ ļ│┤ņśĆļŗż(Table 1). ņ×ÄņŚÉ ĒśĢņä▒ļÉ£ ļģĖĻĘĀļ│æ ļ│æņ¦ĢņØĆ ņ┤łĻĖ░ ļ│æļ░śņŚÉņä£ ņĀäĒśĆ ņ¦äņĀäļÉśņ¦Ć ļ¬╗ĒĢśĻ│Ā ņĀĢņ¦ĆļÉ£ ņāüĒā£ļź╝ ņ£Āņ¦ĆĒĢśņśĆļŗż(Fig. 2B). ņŚ░ļ¦ēņé┤ĒżļŖö ņĢĮņĢĪ ņä▒ļČäņØä Ļ│Āļź┤Ļ▓ī ņŗ£ņäż ļé┤ņŚÉ ĒżĒÖöņŗ£ĒéżĻ│Ā, ņŖĄļÅäņØś ņāüņŖ╣ ļśÉĒĢ£ ņŚåĻĖ░ ļĢīļ¼ĖņŚÉ ĒÜ©Ļ│╝ņĀüņØĖ ļ░®ņĀ£Ļ░Ć Ļ░ĆļŖźĒĢśņśĆĻ│Ā, ņŚ░ļ¦ēņØä Ļ░ĆļæÉĻĖ░ ņ£äĒĢśņŚ¼ ļ░ĆĒÅÉņŗ£Ēé© ņŗ£ņäżņØś ņś©ļÅäņāüņŖ╣ ļ▓öņ£äļŖö 3oC ņØ┤ļé┤ņśĆļŗż(Fig. 3B). ĒŖ╣Ē׳ ņŚ░ļ¦ēļ░®ņĀ£ņØś ņŗ£ņ×æ ņŗ£Ļ░äņØä ņØ╝ļ¬░ ņØ┤Ēøä ņŗżņŗ£ĒĢśļ®┤ ņś©ļÅäļ│ĆĒÖöņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢ£ ļČĆļŗ┤ņØä ņĄ£ņåīĒÖöĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳Ļ░Ć ļĢīļ¼ĖņŚÉ ĒÜ©Ļ│╝ņĀüņØĖ ļ░®ņĀ£Ļ░Ć Ļ░ĆļŖźĒĢĀ Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ĒīÉļŗ©ļÉśņŚłļŗż.

Ļ░ĆņŚ┤ņŚ░ļ¦ē ļ░®ņĀ£ ņŗ£ ĒÖĢņé░ņĀ£ņÖĆ ļ¼╝ņØä Ēś╝ĒĢ®ĒĢśņŚ¼ ņ▓śļ”¼ĒĢ£ Ļ▓ĮņÜ░ ļ░®ņĀ£ĒÜ©Ļ│╝ļŖö ļ¼┤ņ▓śļ”¼ņÖĆ ņ£ĀņØśņĀüņØĖ ņ░©ņØ┤Ļ░Ć ņŚåņŚłĻ│Ā(Table 1), ļ│æņ¦ĢņØś ĒśĢĒā£ ļśÉĒĢ£ ļ¼┤ņ▓śļ”¼ņØś ļ│æņ¦ĢĻ│╝ ņ░©ņØ┤ ņŚåņØ┤ ņ×ÄņØś ņĀäņ▓┤ņĀüņØĖ Ļ│Āņé¼Ļ░Ć ņŗ£ņ×æļÉśņŚłļŗż(Fig. 2C). ļö░ļØ╝ņä£ ņØ┤ņé░ĒÖöņŚ╝ņåīņłśņØś ņŚ░ļ¦ēļ░®ņĀ£ņŚÉņä£ ļéśĒāĆļé£ ļåÆņØĆ ļ░®ņĀ£ĒÜ©Ļ│╝ņŚÉ ĒÖĢņé░ņĀ£ņØś ņśüĒ¢źņØĆ ņŚåļŖö Ļ▓āņØä ņĢī ņłś ņ׳ņŚłļŗż.

ļåŹņé░ļ¼╝ņØś ņäĖņ▓Ö ļ░Å ņåīļÅģņĀ£ļĪ£ ņé¼ņÜ®ļÉśĻ│Ā ņ׳ļŖö ņØ┤ņé░ĒÖöņŚ╝ņåīļŖö ņŗØļ¼╝ ļ│æņøÉĻĘĀņØś ņĀ£ņ¢┤ļź╝ ļ¬®ņĀüņ£╝ļĪ£ ņé¼ņÜ®ļÉśņŚłļŖöļŹ░, ņØ┤ņé░ĒÖöņŚ╝ņåī Ļ░ĆņŖżļź╝ ņØ┤ņÜ®ĒĢśņŚ¼ ļĖöļŻ©ļ▓Āļ”¼ Ļ│╝ņŗż Ēæ£ļ®┤ņØś ĒāäņĀĆļ│æĻĘĀ Ēżņ×Éļź╝ 100ļ░░ ņØ┤ņāü Ļ░Éņåīņŗ£ĒéżĻ▒░ļéś(Sun ļō▒, 2014), ĒåĀļ¦łĒåĀņŚÉ ņāüņ▓śļź╝ ņŻ╝Ļ│Ā E. carotovora subsp. carotovoraļź╝ ņĀæņóģĒĢ£ Ēøä 99 mgņØś ņØ┤ņé░ĒÖöņŚ╝ņåī Ļ░ĆņŖżņŚÉ ļģĖņČ£ņŗ£Ēéżļ®┤ ļ¼┤ļ”äļ│æ ļ░£ļ│æņØä ņÖäļ▓ĮĒĢśĻ▓ī ņ¢ĄņĀ£(Mahovic ļō▒, 2007)ĒĢśļŖö ļ│┤Ļ│ĀĻ░Ć ņ׳ņ¢┤ ņŗØļ¼╝ ļ│æ ļ░®ņĀ£ņĀ£ļĪ£ņä£ņØś ĒÖ£ņÜ®ņŚÉ Ļ░ĆļŖźņä▒ņØä ļ│┤ņŚ¼ņŻ╝ņŚłļŗż.

ļ│Ė ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņŚÉņä£ļÅä ņØ┤ņé░ĒÖöņŚ╝ņåīņłśļŖö ņśżņØ┤ ļģĖĻĘĀļ│æņØś ļ░£ļ│æņØä ņ¢ĄņĀ£ĒĢśļŖö ļŹ░ ņČ®ļČäĒĢ£ ĒÜ©Ļ│╝Ļ░Ć ņ׳ņŚłļŗż. ņØ┤ļ▓ł ņŚ░ĻĄ¼ņØś Ļ▓░Ļ│╝ļŖö ņśżņØ┤ ļģĖĻĘĀļ│æņØś ņ╣£ĒÖśĻ▓Į ļ░®ņĀ£ ļ░®ļ▓ĢņØä ņĀ£ņŗ£ĒĢśĻ│Ā, Ļ░ĆņŚ┤ņŚ░ļ¦ēņØä ņØ┤ņÜ®ĒĢ£ ļ░®ņĀ£ļŖö ļ░£ļ│æņŚÉ ņŖĄļÅäņØś ņśüĒ¢źņØ┤ Ēü░ ņŚ¼ļ¤¼ ņ×æļ¼╝ ļ│æĒĢ┤ņŚÉ ļīĆĒĢśņŚ¼ ļ░£ļ│æĒÖśĻ▓ĮņØä ņ¢ĄņĀ£ĒĢ©ņ£╝ļĪ£ņŹ© ļ░®ņĀ£ ĒÜ©Ļ│╝ļź╝ ļŹöņÜ▒ ļåÆņØ╝ ņłś ņ׳ņØä Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ĻĖ░ļīĆļÉśļ®░, Ēśäņ×¼ ĒÖöĒĢÖļåŹņĢĮļ¦īņ£╝ļĪ£ ĒśĢņä▒ļÉ£ ņśżņØ┤ ļģĖĻĘĀļ│æ ļ░®ņĀ£ņĀ£ ņŗ£ņןņØä ņ£ĀĻĖ░ļåŹņŚģņ×Éņ×¼ļĪ£ ļīĆņ▓┤ĒĢĀ ņłś ņ׳ņØä Ļ▓āņ£╝ļĪ£ ĻĖ░ļīĆļÉ£ļŗż.

Acknowledgments

This work was carried out with the support of Cooperative Research Program for Development of Industrialization Technology to Crop Viruses and Pests(Project No. 120086052HD030), Korea Institute of Planning and Evaluation for Technology in Food, Agriculture and Forestry, Korea.

Fig.┬Ā1.

Symptomatic development of downy mildew on cucumber leaves. Each picture represents early (A), mid- (B), and late (C) stage of disease progress of downy mildew. Pictures were obtained 3, 7, and 15 days post-infection for early, mid-, and late disease symptoms, respectively.

Fig.┬Ā2.

Suppression of downy mildew disease by the treatment methods of chlorine dioxide in plastic greenhouse test. Pictures for disease symptoms of downy mildew were taken at 28 days post-infection: leaf spraying (A), thermal fogging (B), thermal fogging only with diffusig agent (C), and untreated control (D).

Fig.┬Ā3.

Changes in humidity (A) and temperature (B) in plastic greenhouses before and after treatment with chlorine dioxide by thermal fogging and leaf spraying. The arrow indicates when chlorine dioxide was treated.

Table┬Ā1.

Effect of treatment methods using chlorine dioxide for the control of downy mildew on cucumber in plastic greenhouse

| Treatment | Disease severity (%) | Control efficacy (%)a |

|---|---|---|

| Leaf sprayingb | 22.5┬▒1.2 bc | 41.5 |

| Thermal foggingd | 7.4┬▒1.0 c | 80.9 |

| Thermal fogging only with diffusing agent | 37.5┬▒0.6 a | 2.6 |

| Untreated control | 38.5┬▒0.8 a | - |

References

Benarde, M. A., Israel, B. M., Olivieri, V. P. and Granstrom, M. L. 1965. Efficiency of chlorine dioxide as a bactericide. Appl. Microbiol. 13: 776-780.

Chang, T. H., Lim, T. H., Kim, I. Y., Choi, G. J., Kim, J.-C., Kim, H. T. et al. 2000. Effect of phosphorous acid on control of phytophthora blight of red-pepper and tomato, and downy mildew of cucumber in the greenhouse. Korean J. Pestic. Sci. 4: 64-70. (In Korean)

Chen, Z., Zhu, C., Zhang, Y., Niu, D. and Du, J. 2010. Effects of aqueous chlorine dioxide treatment on enzymatic browning and shelf-life of fresh-cut asparagus lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.). Postharvest Biol. Technol. 58: 232-238.

Choi, G.-J., Yu, J.-H., Jang, K.-S., Kim, H.-T., Kim, J.-C. and Cho, K.-Y. 2004. In vivo antifungal activities of surfactants against tomato late blight, red pepper blight, and cucumber downy mildew. J. Korean Soc. Appl. Biol. Chem. 47: 339-434. (In Korean)

Choi, S., Beuchat, L. R., Kim, H. and Ryu, J. H. 2016. Viability of sprout seeds as affected by treatment with aqueous chlorine dioxide and dry heat, and reduction of Escherichia coli O157: H7 and Salmonella enterica on pak choi seeds by sequential treatment with chlorine dioxide, drying, and dry heat. Food Microbiol. 54: 127-132.

Han, Y., Linton, R. H., Nielsen, S. S. and Nelson, P. E. 2001. Reduction of Listeria monocytogenes on green peppers (Capsicum annuum L.) by gaseous and aqueous chlorine dioxide and water washing and its growth at 7oC. J. Food Prot. 64: 1730-1738.

Kim, G. H., Park, J. Y., Cha, J. H., Jeon, C. S., Hong, S. J., Kim, Y. H. et al. 2011. Control effect of major fungal diseases of cucumber by mixing of biofungicides registered for control of powdery mildew with other control agents. Korean J. Pestic. Sci. 15: 323-328. (In Korean)

2009. Microbial changes in hot peppers, ginger, and carrots treated with aqueous chlorine dioxide or fumaric acid. Korean J. Food Preserv. 16: 1013-1017. (In Korean)

Kim, Y.-K., Ryu, J.-D., Ryu, J.-G., Lee, S. Y. and Shim, H.-S. 2003. Control of downey mildew occurred on cucumber cultivated under plastic film house condition by optimal application of chemical and installation of ventilation fan. Korean J. Pestic. Sci. 7: 223-227. (In Korean)

Kim, Y.-K. Park, S.-H., Um, D.-O., Hong, S.-J., Cho, J.-L., Ahn, N.-H. et al. 2018. Control of cucumber downy mildew using resistant cultivars and organic materials. Res. Plant Dis. 24: 153-161. (In Korean)

Korean Society of Plant Pathology. 2009. List of Plant Disease in Korea. 5th ed The Korean Society of Plant Pathology, Suwon, Korea. pp. 853 pp pp.

Lebeda, A. and Cohen, Y. 2012. Fungicide resistance in Pseudoperonospora cubensis, the causal pathogen of cucurbit downy mildew. In: Fungicide Resistance in Crop Protection: Risk and Management, ed. by T. S. Thind, pp. 44-63. CABI, Wallingford, UK.

Lee, J.-S., Han, K.-S., Lee, S.-C. and Soh, J.-W. 2013a. Screening for resistance to downy mildew among major commercial cucumber varieties. Res. Plant Dis. 19: 188-195. (In Korean)

Lee, S., Moon, H.-K., Lee, S.-W., Moon, J.-N., Lee, S.-H. and Kim, J.-K. 2013b. Enhanced antimicrobial effectiveness of Omija (Schizamdra chinesis Baillon) by ClO2 (chlorine dioxide) treatment. Korean J. Food Preserv. 20: 871-876. (In Korean)

Lee, S. Y., Weon, H. Y., Kim, J. J. and Han, J. H. 2013c. Cultural characteristics and mechanism of Bacillus amyloliquefacien subsp. plantarum CC110 for biological control of cucumber downy mildew. Korean J. Pestic. Sci. 17: 428-434. (In Korean)

Lee, S. Y., Weon, H. Y., Kim, J. J. and Han, J. H. 2013d. Selection of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens CC110 for biological control of cucumber downy mildew caused by Pseudoperonospora cubensis. Korean J. Mycol. 41: 261-267. (In Korean)

Mahovic, M. J., Tenney, J. D. and Bartz, J. A. 2007. Applications of chlorine dioxide gas for control of bacterial soft rot in tomatoes. Plant Dis. 91: 1316-1320.

Mari, M., Bertolini, P. and Pratella, G. C. 2003. Non-conventional methods for the control of post-harvest pear diseases. J. Appl. Microbio. 94: 761-766.

Meng, R., Han, X. Y., Wu, J., Zhao, J. J., Lu, F. and Wang, W. Q. 2017. Resistance dynamics of Pseudoperonospora cubensis to metalaxyl and azoxystrobin and control efficacy of seven fungicides against cucumber downy mildew in Hebei Province. J. Plant Prot. 44: 849-855.

Ministry of Agriculture, Food Rural Affairs. 2020. The Numerical Statement of Agriculture. Food and Rural Affairs, Sejong, Korea. pp. 98-99.

National Agricultural Products Quality Management Service. 2021. List of Organic Materials. National Agricultural Products Quality Management Service, Gimcheon, Korea.

National Institute of Agricultural Sciences. 2018. Pesticide Registration Test: Pesticide Efficacy and Crop Safety Guidelines, Fungicide Section.. National Institute of Agricultural Sciences, Wanju, Korea. pp. 423-425.

Park, J.-W., Kim, Y.-K., Park, S.-H., Hong, S.-J., Shim, C.-K., Kim, M.-J. et al. 2016. Effect of organic materials and the removal of apical shoot on controlling cucumber downy mildew. Korean J. Org. Agric. 24: 919-929. (In Korean)

Park, S.-D., Kwon, T. Y., Lim, Y.-S., Jung, K. C. and Choi, B.-S. 1996. Disease survey in melon, watermelon, and cucumber with different successive cropping periods under vinylhouse conditions. Korean J. Plant Pathol. 12: 428-431. (In Korean)

Park, S. S., Sung, J. M., Jeong, J. W., Park, K. J. and Lim, J. H. 2012. Efficacy of electrolyzed water and aqueous chlorine dioxide for reducing pathogenic microorganism on Chinese cabbage. Korean J. Food Sci. Technol. 44: 240-246.

Roberts, R. G. 1994. Integrating biological control into postharvest disease management strategies. Hortic. Sci. 29: 758-762.

R Core Team. 2017. R foundation for statistical computing ver. 3.4.0. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria.

Ryu, S.-H. 2007. Effects of aqueous chlorine dioxide against Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Listeria monocytogenes on broccoli served in foodservice institutions. J. Korean Soc. Food Sci. Nutr. 36: 1622-1627. (In Korean)

Savory, E. A., Granke, L. L., Quesada-Ocampo, L. M., Varbanova, M., Hausbeck, M. K. and Day, B. 2011. The cucurbit downy mildew pathogen Pseudoperonospora cubensis. Mol. Plant Pathol. 12: 217-226.

Sharma, D. R., Gupta, S. K. and Shyam, K. R. 2003. Studies on downy mildew of cucumber caused by Pseudoperonospora cubensis and its management. J. Mycol. Plant Pathol. 33: 246-251.

Sun, S., Lian, S., Feng, S., Dong, X., Wang, C., Li, B. et al. 2017. Effects of temperature and moisture on sporulation and infection by Pseudoperonospora cubensis. Plant Dis. 101: 562-567.

Sun, X., Bai, J., Ference, C., Wang, Z., Zhang, Y., Narciso, J. et al. 2014. Antimicrobial activity of controlled-release chlorine dioxide gas on fresh blueberries. J. Food Prot. 77: 1127-1132.

Urban, J. and Lebeda, A. 2006. Fungicide resistance in cucurbit downy mildew: methodological, biological and population aspects. Ann. Appl. Biol. 149: 63-75.

Yao, K.-S., Hsieh, Y.-H., Chang, Y.-J., Chang, C.-Y., Cheng, T.-C. and Liao, H.-L. 2010. Inactivation effect of chlorine dioxide on phytopathogenic bacteria in irrigation water. J. Environ. Eng. Manage. 20: 157-160.

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

-

- 0 Crossref

- 0 Scopus

- 2,954 View

- 75 Download

- ORCID iDs

-

Byung-Ryun Kim

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5257-184X - Related articles

-

Control of Cucumber Downy Mildew Using Resistant Cultivars and Organic Materials2018 ;24(2)

Environment-Friendly Control of Pear Scab and Rust Using Lime Sulfur2018 ;24(1)

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print